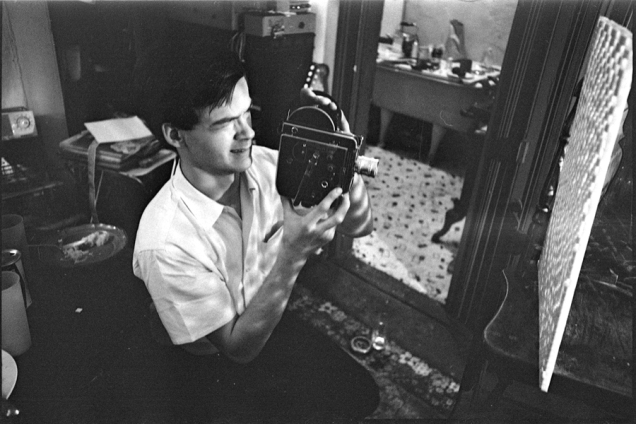

Autoportraits by Giovanni Di Domenico (2017) – used with permission

Born in Rome in 1977, pianist Giovanni Di Domenico spent much of his youth in Africa as well as Italy, absorbing a multitude of musical styles – with folk traditions, opera, prayer calls, classical repertoire, jazz and punk all shaping his expansive approach to sound. In his twenties Di Domenico enrolled in the prestigious Santa Cecilia music conservatory in Rome and later the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, undertaking piano studies with a free-spirited, rebellious ethic. Now resident in Brussels, he has garnered much respect for his energetic, inventive musicality – in recent years he has honed his talents in solo and group playing contexts with Akira Sakata, Jim O’Rourke, Tatsuhisa Yamamoto, John Edwards, Alexandra Grimal, Keiji Haino, Manuel Mota and Chris Corsano among others. Through his label Silent Water, he has showcased the work of frequent collaborators including Norberto Lobo, Pak Yan Lau and João Lobo as well as the Japan based trio Delivery Health – comprising Domenico, O’Rourke and Yamamoto.

A new LP, Insalata Statica, pushes Di Domenico’s capabilities as a composer into the foreground. It also reflects a hitherto under-acknowledged pop sensibility. Written and performed almost in its entirety by Di Domenico, the album takes listeners from passages of melancholic introspection through to fuzz-laden melodic exuberance. Those who have witnessed Di Domenico in a live performance setting recognise the expansive variety of tonalities and voices he is able to express across a range of keyboard based instruments, including Rhodes, Hammond and grand piano – all of which feature on the album. But Insalata Statica also sees Di Domenico returning to his first instrument, the guitar, as well as calling on guests to lend extra elements to the kaleidoscopic sound – with Niels Van Heertum on euphonium, João Lobo on drums, Jordi Grognard on clarinets, harpist Vera Cavallin and Ananta Roosens on trumpet.

Insalata Statica’s flowing, shifting harmonies, rhythms and textures are deftly arranged – often blurring lines between a wide variety of acoustic and electronic instrumentation. While largely recorded in the studio in his current city of residence, it seems only fitting that for a peripatetic musician such as Di Domenico the album should suggest the experience of travel throughout its ever shifting movements. Listening to Insalata Statica, one can imagine the character of different landscapes – and their effect on mood and energy. The music seems to convey the haze of early departure; the romance of new climates; sleepy intervals and the hectic rush of transit; the feeling of sudden inspiration and the lasting traces of memory.

Moving through delicate motifs for horns, woodwind, percussion, harp, guitar and electronics into more stately piano-led choruses and even hectic, Hammond-led jazz sections, there are evocations of Franco Battiato’s 70s albums, Brazilian folk flourishes, the spacious, harmonically rich jazz of ECM recordings and oddball pop. Ushering such influences into a vibrant whole, revealing a skilful ear and an ability to blend instrumental timbres and melodic lines in surprising ways, Insalata Statica has a charm all its own.

I spoke with Di Domenico about his musical activities over the years and the process of writing and recording Insalata Statica.

Insalata Statica was five years in the making. Was there a specific compositional idea behind it from the beginning that you were interested in exploring?

I did not have a specific idea before writing the music for it. I was actually writing for another band at that point, and was planning on using that material for them. Then things changed and it made sense to me to use that material as a whole, for a single piece. The actual music, six different ‘tunes’, were written in a couple of days, then it took me five years, to arrange, record and edit everything and to turn it into an album. Insalata Statica means ‘static salad’ in Italian. It’s like I prepared the musical salad in no time and then took a long time to dress it.

Was the length of time it took a matter of figuring the transitions – were there different versions with those original tunes ordered differently? Or was it a more linear process that other demands and travelling simply took you away from for extended periods?

I guess it was a bit of both: a lack of time, that without my wanting it to, ended up lengthening the process of arranging and recording – but also way too many ideas during the same process. In the end I had to stop, or else I felt it could have gone on forever.

Basically, when I wrote the material and then decided what to do with it, I knew it could work but did not know quite how – making the songs separate entities or else try to make it into a whole. I think the order of the different passages came pretty easily and quickly. Then I thought about calling it Insalata Statica. The name comes from a joke made by an old friend: he was always saying that I was preparing ‘static’ salads. I thought that was a brilliant name and I had to use it! I thought it was ideal to have a more static beginning that slowly unfolds, taking different twists and turns, to reach a much less static ending. In reality the record isn’t static at all, it moves a lot and has a lot of rhythmical and harmonic layers. I was, and still am really, a lot into Jim O’Rourke’s The Visitor during that period, which certainly helped shape my approach.

I’m interested in how the piece transformed and how your thinking may have changed throughout that long a period.

I usually worked for several days on it, then let some days pass, then listened to it again to see what could be changed, added, or thrown away. I was hearing too many different things and at times I could not make up my mind. I knew, with the way I was approaching the whole thing, that a very simple idea could take me very far, if I could just give the right weight to that idea.

Sometimes other records I was into at that moment, or other stuff I was doing would give me other ideas and I had to hold them till the moment I was sure what to do with them. Other times I would just start to ‘jam’ with the tracks that were already there and something just right came up that had to be used no matter what. But I had to stick at this. At times I got fed up with it and wanted to throw everything in the garbage. I then left it for a couple of months unattended and went straight back to it. I could not leave it, it had to be finished.

As with much of your work, you are exploring an array of approaches to keyboard instruments – electronic textures, Rhodes, organ drones, Hammond, reflective interludes, all weaved together without a jarring effect. Not an easy feat. But there’s a whole orchestra here. I can also hear guitar. At first I thought some technique applied to the inside of the piano might have been behind some of the pizzicato sounds because some of the instrumentation blurs wonderfully in timbre and colour. Did you play most of the instruments on the record?

I played almost everything, except euphonium, clarinet, harp and some drum parts. Yes it’s a guitar! I am actually glad that you thought it was plucked piano, that’s a great idea you have given me – albeit quite difficult to make it sound like a guitar should sound, I guess.

Me and the guitar have a long history, actually. That’s the first instrument I learned to play, and I left it behind as I was discovering the piano, the drums and everything else I could put my hands on. But it stayed a very important instrument for me, although I never dared to play it again, until the point when I was in Japan playing with Jim [O’Rourke] and Tatsu [Yamamoto] and all. Jim asked me ‘Do you play guitar? You should!’ This was a kind of revelation, in the sense that it gave me the guts to do it, and although I am not a very good guitar player I regained the thrill of playing it and I liked it a lot. This happiness led me to want to do this record, that’s why I think it sounds like it does. I was really having fun!

The tactile aspects of the instrumentation seem very important to you – I can’t picture you using midi controls with computer software. When I’ve seen you play live, you are often moving between piano and Rhodes, between the outside and the inside of the piano.

In the beginning, while I was writing the music, I just had piano, Rhodes, Hammond, other keyboards and also electric guitar and electric bass – all within reaching distance. I would just pass from one to the other in a very simple but deep way, sometimes not caring too much about the precision and cleanness of things. That is why at times it sounds ‘loose’. You are right, I have never used any midi or software based computer thing. I am not able to do so. I need this tactility, which you mention. I need to put my hands on the instruments and try to do everything that I ‘hear’ through actual manipulation.

But another part of the process that excites me more than words can say is the editing and mixing side of things. I really like to sit down and listen to things while just imagining sounds changing their colour, contrast and weight – a bit like Photoshopping a picture. And through that a lot of the qualities of a single instrument can change. For me it is important that this production process is a vital part of the compositional development of the music.

You have said that the album encompasses most of your strongest influences. Rather than simply ask what those are, I’m interested in how easily or otherwise you found that you could weave them together into something distinctly your own. Do you think there is a common denominator among those, apparently various, influences that allows them to combine? Or connections between things that only occurred to you after some time?

There’s a fundamental thing that connects those ‘influences’ – not the specific influences but the act of thinking about them – and the fact that this is my first solo LP: I passed beyond any sense of pressure I might have felt before, of having to stick to one style, to put it crudely. I said to myself that I had to do what I like most – that is, to put all that I hear into organised sounds. Although, if I had to enumerate all those influences and styles I’d still find that there are some very significant ones that are missing from this record. For example, the most radical and fierce ways of playing, like I do with Akira Sakata – and the more extreme sounding ones. That stuff I like to listen to and make my own as well.

I did what I had to do and it came so easily that soon I forgot about all the doubts and insecurities that have been lingering since, basically, always.

Where do you think those particular doubts come from?

I’ve taken kind of a strange path in music. I haven’t done anything else since I was 12 but I’ve moved along, taking many different roads, constantly immersing myself of course but not quite finding my own voice, or voices. Now if I go backwards I am happy with all of this but some time ago I found myself getting frustrated for not having discovered something before – that same something, which at that precise moment was freaking me out because of its beauty!

When making this record, it was not difficult to combine everything. It all made a lot of sense to me finally. Of course, it might be that I’m saying all this because I just turned 40, and perhaps I finally feel mature! These things took time to find their shape, but once they did all the rest came pretty quickly and easily.

This is your first solo album under your own name, made largely in isolation. Despite the obvious pleasure that editing and mixing has given you, do you still prefer to be playing amongst other musicians?

I don’t really treat it all that differently – playing alone, composing, recording and staying in the studio as much as I can by myself, and playing with others. I mean Bonjintan [jazz quartet with Akira Sakata, O’Rourke and Yamamoto] is great. Playing is always great when it’s with great people, it gives me a lot and I would never drop it. But I’ve gotten more and more picky in choosing my musical pals and I don’t have a problem with saying no to something that I just don’t ‘hear’.

I have done other solo albums, but I always used a pseudonym. I wanted them to be only electroacoustic and in keeping with a certain niche, or style, or whatever. I don’t hate them but I clearly feel that they were part of this research and I can hear that they are very naïve in a way. Now I probably would not release them.

Tell me a bit about your experiences of going to school to study piano and what your feelings were/are about the value of that – as opposed to the learning you continue to do in the context of relentless live performance and collaboration. I know some musicians are not keen on studying music in an academic sense.

I didn’t go to music school until I was 24. I went to the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, where I studied jazz piano. That conservatory is famous for its adherence to jazz tradition, especially bebop. Before that I spent one year at the Santa Cecilia conservatory in Rome where I studied composition. That was 1998, but I only lasted a year, as I was not really keen on doing solfège. I was always very rebellious when it came to academia. I don’t even have a high school degree. And so they kicked me out, I was expelled. But during this time I was playing in all sorts of punk, surf and hardcore bands in Rome. There was quite a scene back then, a lot of groups that didn’t go anywhere really but that shaped me a great deal – although I didn’t realise that until much later.

As I was telling you before, for a long time I felt frustrated for having taken what I see as a somewhat tortuous path through music. When I arrived at the conservatory in Holland, I remember being so angry at myself because I was hearing very young musicians of 18 or so playing their asses off. I thought I’d lost so much time. And in The Hague there is the amazing Sonology department, but at that time I was not really aware of what it is. If I were there now, I would spend more time in that facility than practising scales and chords!

But I got over all that as I continued, discovering that all the things I had in me came from that same path. I accepted it and started to like it and make it my strength. Of course I feel it’s still in progress, it will never end. The most important thing I gained from those academic years was some of my very best ‘musical’ friends – and overall just friends – having grown up together, having tried so many different things and learned things about producing/recording etc.

The resources in that place were really amazing. But I also remember having an instant allergy to courses dealing with the business side of the profession. I just thought that was total crap, that I should not get even close to that sort of thing, I still think so! I have the feeling that my aversion to ‘business’ comes from my aversion to ‘being there’, to exposing myself to the infinite tentacles of the culture of promotion. I mean I am already doing a job that exposes me: I create something that people are supposed to consume and enjoy, but I’d rather be known and, if fortunate enough, appreciated for my music, not for how much it sells or anything like that. I know there’s a contradiction in all this, but I just can’t get too much into the social media culture, even for promoting my work. I would certainly not put anything of my private life out there. I feel my music would be affected if I did so. I absolutely cannot compromise on that.

Yet you do run your own label, Silent Water, which is putting out releases fairly regularly. What was the impetus for doing that and what are some of the difficulties and benefits you have experienced?

The idea of having a label has always been there. But the timing to set up Silent Water was a bit of a coincidence. I always had the idea that I would set up ‘my label’ with my first ‘solo’ record, then in 2012 I had a disagreement with another label owner about the release of one of my LPs. So I decided, ‘Fuck it, I am going to do it myself’. I was not prepared for that, though, so that LP had the SW002 catalogue number!

It just makes everything easier for me to have my own label to put out my own music. For a period I was thinking that it would have been the worst idea to put out things on my own label – it seems too ‘simple’. Then I would think of all the great musicians since the ’70s who have started their own record companies, and also see the freedom that being your own boss brings you. I think it’s a great way to push yourself, to always go further and feed your ideas and projects. Of course I was lucky enough to have some money to put into it, and to have folks around me who agreed to paying something when it was needed – and understood that the profitability of all this was going to be almost non-existent. Neither I nor we will get rich from Silent Water, but that’s exactly what I like about it. I just want to be able to pay for the next record. Now, with 15 releases in five years, I have to say it has gone much further then I could ever expect.

You are now planning to do live shows around Insalata Statica with an eight-piece band. How do you think you might approach it in this different context?

After all the time I spent on Insalata Statica, I thought it would be a shame not to tour it around, and the first thing that was clear to me was that it had to be with a band. For technical reasons: the fact that some parts of the record have over 100 layers makes it impossible to play it live by myself, at least without using samples and pre-recorded tracks. But I can’t do that! Insalata Statica is a very ‘lived’ piece. I simply can’t think about having it be played by a software. So I decided I was going to put together a band for it, with the same people that helped me do the record – and the addition of a bass player and a guitar player. That prospect excites me a lot, as I have to rewrite or at least rethink many of the parts, to be able to make it sound like it should. In any case it will sound somewhat different. I’ve realised I will have to change certain parts of the orchestration but I’m curious and looking forward to hearing it. After having been ‘inside’ this music for so long, I want to get ‘outside’ of it, and to share it with others. There is the social reason too: I want to give something back to the great musicians that helped me so much. Although it’s going to be a financial disaster, travelling with eight people with instruments in Europe, I don’t care and I want to do it no matter what.

Insalata Statica is released by Silent Water (https://silentwaterlabel.com/).